Host is a cinematic marker like no other of how drastically the last 12 months have changed the world. A year ago, the low-budget horror film – about a group of friends who enact a seance over Zoom for a laugh during lockdown – did not exist, not even as an idea in the mind of director Rob Savage. Nor did the pandemic that forms the movie’s distressing real-life backdrop, with Covid-19 at that point limited to just a handful of reported cases near the wet markets of Wuhan. Zoom was also largely unknown back then: it was not until March, when countries retreated into quarantine, separating friends and families, that the video conferencing tool became part of the fabric of our lives.

More like this:

– Twelve films to watch in December

– An explosive final role for a film icon

– The strangest horror of its era

“Covid changed the entire way we interact so quickly,” says Savage, who recalls the strangeness of how “we all started talking about infection rates and death tolls the way we used to talk about the weather.” The director – who before Host, had only a few short films, commercials and TV credits to his name – initially planned to “eat too much, drink too much and play The Last of Us” through lockdown, but he soon found himself in desperate need of a distraction. “It was a project to stop me going mad,” laughs Savage. Instead, it became a phenomenon: Host, the word-of-mouth masterclass in frightful suspense, made almost overnight, that bottled the panic and paranoia of our pandemic year.

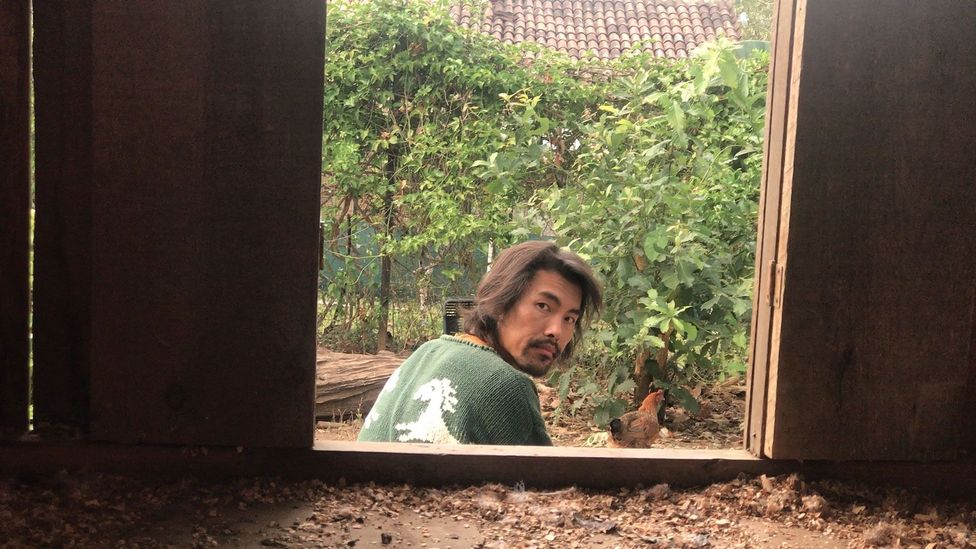

Host is a supernatural chiller, in which a seance conducted on Zoom during lockdown goes awry (Credit: Vertigo Releasing)

Host’s smart concept and imaginative scares – utilising internet glitches, face filters and other facets of our largely digital post-coronavirus existences – made it a cult sensation from the moment it launched on specialist horror streaming service Shudder in July. Immediately, the horror community started singing its praises while soon, more mainstream outlets were taking notice, from Good Morning America to the New York Times, who heralded it a horror that “speaks to our moment of uncertainty.” The film rocketed Shudder to record audience figures (the service reported breaking 1 million subscribers shortly after Host’s release), made a horror A-lister of its director (Savage was quickly snapped up by acclaimed production company Blumhouse to direct three new movies) and sparked so much interest that on Friday, the film will enter UK cinemas for a limited theatrical run.

“I was really worried that people would dismiss the film, that they’d think it’s opportunistic or gimmicky. Luckily, we connected,” says Savage. The extent of that connection with viewers raises questions for the film industry and beyond, as creators of movies, literature, video games and more attempt to work out what sort of stories to tell in a post-Covid-19 world. Do audiences want entertainment that distracts them from the stresses of the pandemic? Or does Host teach us that there’s a hunger for films, novels and so on that address our current global situation, helping us work through some of our emotions, frustrations and fears related to the New Normal?

There’s certainly a precedent for the latter. Pop culture has a long history of being a space for audiences to work out their collective traumas. “Books and films can let us wrap our heads around things we’re going through by putting it into metaphor,” says the novelist and screenwriter C Robert Cargill, known for his work on Marvel’s Doctor Strange and lauded 2012 horror Sinister. “Horror cinema in particular has a long tradition of this. Horror works best as allegory – it allows us to take our deepest fears and turn it into a monster that has a face, so we can literally look our fears in the eye, confront them and hopefully overcome them. The Shining is really a story about alcoholism, and how it breaks down the American family. Poltergeist is about how we feel safe in suburbia, but you’re not as safe as you think you are. Great horror is always wrestling with something else.”

Host falls into this category by taking the sense of disconnection caused by quarantine, torn apart from the people we care about, and pouring it into an 80-minute supernatural chiller. Lights start to flicker. The seance goes awry. A demonic presence begins to wreak havoc. So far, so familiar for seasoned horror movie watchers.

Netflix’s short film anthology Homemade has been one of a number of quickfire responses to the pandemic in TV and film (Credit: Netflix)

What Savage’s film did that was new and devastatingly relatable was to make a seance film in which characters stare helplessly into digital devices, worrying about their friends as an invisible enemy began to run rampant – something we’ve all experienced in 2020. The true terror of Host was in its eerie echo of our own lives. “I think people go to the cinema to be seen,” says the director. “There’s something really valuable and worthwhile about reflecting the strange new texture of our lives on screen as a way of letting people process it.”

“When the pandemic hit, we got all sorts of requests for movies about viruses to be added to the service,” recalls Shudder head honcho Craig Engler, who suggests that movies like Host have a societal benefit. “People like to experience and work through things they’re going through vicariously through movies. It helps them negotiate with their own trauma, and they become less scary in real life.”

The new wave of Covid dramas

It’s not just within horror that storytellers have begun reacting to the pandemic. Since March, we’ve had sitcom specials (Parks and Recreation, 30 Rock, Mythic Quest) and unexpected sequels incorporating Covid-19 upheaval (Borat 2). Both Netflix (short film collection Homemade, anthology series Social Distance) and HBO (poorly-reviewed monologue show Coastal Elites) have tried their hands at pandemic dramas, too. NBC’s Connecting, Freeform’s Love in The Time of Corona: the list goes on. Existing TV favourites like Grey’s Anatomy and This Is Us have begun incorporating Covid-19 storylines, too, suggesting it’s not just new narrative art that will choose to address it.

Major movie studios are also getting in on the act. Adam Mason’s dystopian thriller Songbird, set in 2024, when the world is battling a mutated form of the virus, wrapped production recently, and there’s even a pandemic-themed romantic comedy en route: the Anne Hathaway-starring Lockdown, about a jewellery heist at Harrods while the famous London store is shut because of a coronavirus outbreak. In the world of theatre, meanwhile, lockdown has given rise to the Zoom play, with US playwright Richard Nelson among those to have created new work responding to the crisis: in addition to Nelson’s trilogy of digital shows centring on his old characters the Apple Family, we’ve also seen a selection of timely and social distancing-friendly one-person pieces, such as the Viral Monologues series of short plays. A wave of films, novels, plays and more about the pandemic now feels inevitable.

History, however, suggests that most of them will struggle to be embraced, failing to strike the narrative nerve that Host has. “If you go back in history, every time there’s been a pandemic, very little truly great art has come out after the fact about the pandemic,” says Cargill. “There is no great novel about the Spanish Flu. There is no great pandemic movie from the pandemic of 1967-68.” Instead, he predicts pop culture will counteract the grimness of the situation by leaning into lighter programming full of fun and frivolity. “If you look at the media of the late [1910s] and early 1920s, there’s a lot of escapism there.”

Borat 2 incorporated the Covid-19 crisis into its story framework at the last minute (Credit: Amazon)

Writing stories about pandemics is hard, especially for blockbuster movies and mainstream TV shows, because contagions like Covid-19 are invisible enemies whose devastation isn’t loud and exciting, but quiet and gruelling: “the most boring apocalypse you could imagine,” as Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker recently put it. There are few explosions and hordes of panicked people running through the streets. Instead, pandemic stories are by default tales of monotony and slow decay. That’s not to say it is impossible to make great art about real-life mass disease: you can look all the way back to Daniel Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year, about 1655’s bubonic plague outbreak in London, while, more recently, the AIDS pandemic of the 1980s sparked a wave of acclaimed and seminal work, from Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart to Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia. But the relatively poor reviews for (and only mild audience interest in) most Covid-19 stories so far points to a challenge ahead for writers wishing to react to this moment in history.

Covid-19 will undoubtedly have an impact on storytelling in the future. But those changes may be micro rather than macro. “2020 is going to be this big speed bump in culture, like 9/11 or a war, where even if your movie isn’t directly about it, you have to acknowledge that it happened within the universe of your story,” screenwriter and author John August (Aladdin, Charlie’s Angels) told me earlier this year. “Take Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story. Slide that movie two years forward, and that couple would have made it through Covid-19 in New York. It would feel weird to not acknowledge that family had gone through that challenge together.” The problem facing storytellers wanting to make movies about the pandemic is what he describes as “the fish-in-an-aquarium problem: it’s hard to see the water.” Right now, we’re so immersed in Covid-19 as a culture that telling truly gripping or interesting stories about it is tricky to do.

Which perhaps explains the success of Host. “It’s not a great pandemic film – it’s a great film whose story coincides with the pandemic,” says Engler. “It works because it deals with the frustration of trying to deal with Zoom calls... with a horror element added in,” adds Cargill. “That’s what works about it, not the fact that it takes place within the pandemic.” Instead of telling the story of the coronavirus crisis, it zeroes in on one relatable fact of it. “Successful pandemic movies will let viewers identify fine details of what daily life is like right now: not getting the brands of food we like in grocery deliveries, small things like that. It’s that which will connect with audiences.”

The most successful films dealing with the pandemic may not be obviously pandemic-themed at all. Stories set during the Covid-19 crisis are in-demand at studios right now, but how many of them will make it to the screen is debatable: the length of time it takes to make most movies, coupled with the unpredictable nature of a pandemic, makes it difficult for movie execs to know what sort of market they’re going to be arriving in. Tonally and narratively, assumptions a fiction film makes about the virus could be totally out of date by the time a movie’s ready to be released. Instead, it’s likely we’ll see a lot of pandemic movies that aren’t pandemic-related on the surface, but use different guises to explore the feelings and societal issues Covid-19 has foregrounded: subjects like isolation, separation, governmental incompetence and humility in the face of nature.

Savage is curious about what comes next. “I’m glad Host has been cathartic for some people, and I’m sure other great filmmakers are readying other projects that they hope will be cathartic, too,” he says. “You make films to reflect the world around you. What we’re going through already feels pretty cinematic: we’re living in a dystopian movie. I’m intrigued by how setting things in this New Normal will make old ideas feel fresh.” Covid-19 has changed almost everything about our existences in 2020. You can expect it to change the sort of storytelling we see on screens in 2021, too.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"that" - Google News

December 01, 2020 at 01:11PM

https://ift.tt/2JefKQP

The Zoom horror that was 2020's most timely hit - BBC News

"that" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3d8Dlvv

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar